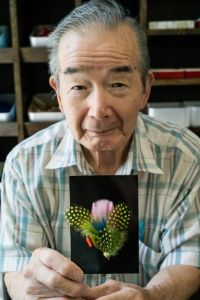

Mr. Meboso Hachirobei is carrying on the family tradition of tying flshing flies and lures in Kanazawa, Japan.

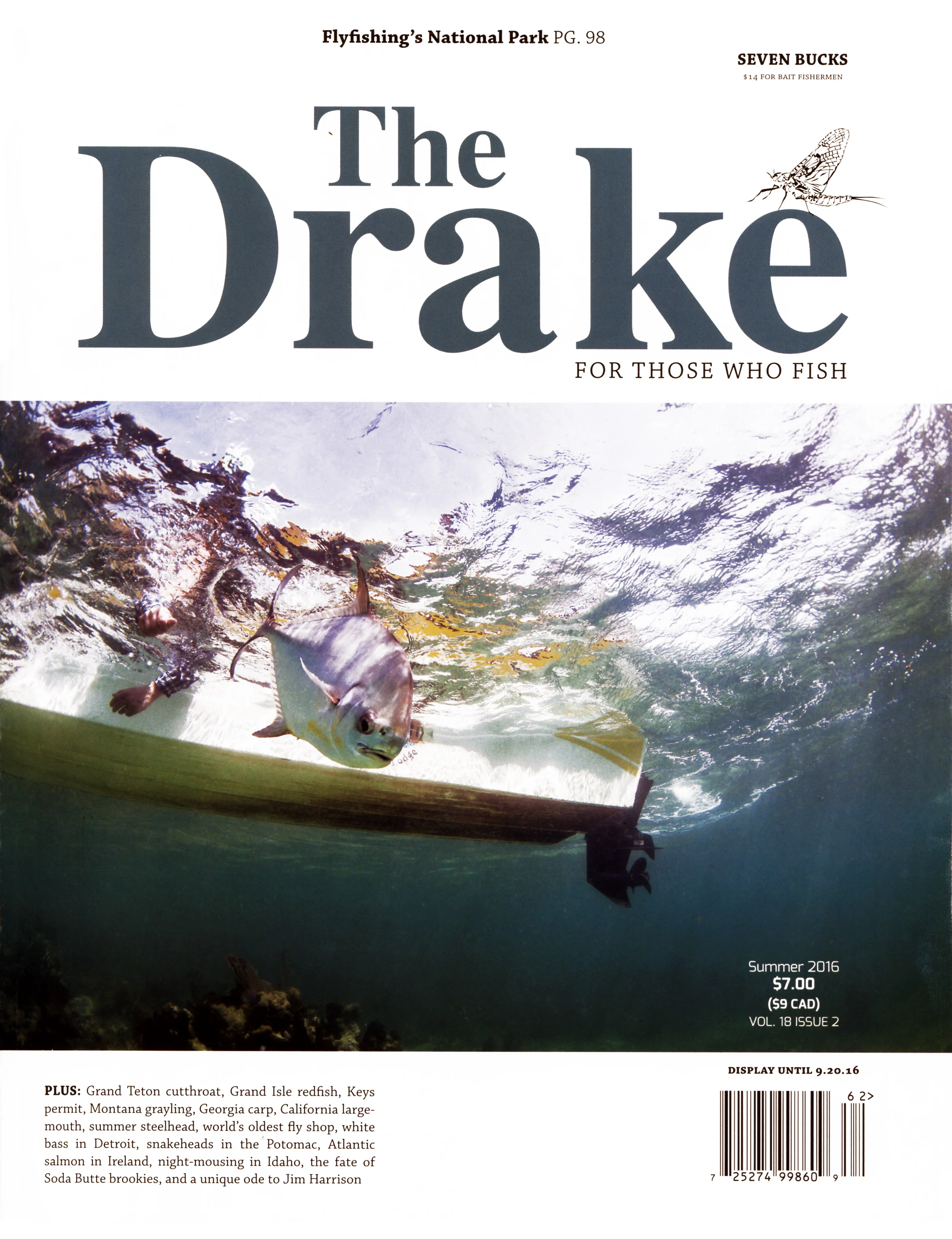

The world's oldest fly shop

Fly-Fishing in Kanazawa

“Do you like the smell of fish?”

Mr. Koshida posed the question as we walked together through the Ohmicho market, a briny smelling mega market of glistening seafood located in the heart of Kanazawa. As a matter of fact, I answered, I’m a fisherman and do like the smell of fish.

“I too like the smell of fish,” said Mr. Koshida, who was 65 years old and wore glasses, khaki pants, a grey polo shirt and had a Kanazawa Goodwill Guide ID card hanging around his neck. Mr. Koshida had arrived at my ryokan at precisely 10 a.m., just as we planned over email.

This story originally appeared in the summer 2016 issue of The Drake.

As we strolled past stalls selling giant prawns, lobsters, octopus, crabs and wild potatoes from the surrounding mountains, Mr. Koshida presented me with a small gift: a keychain-sized, multi-hued temari ball, stitched together like a baseball with wadded-up pieces of silk fabric.

“My mother made this,” he said. “This is emblematic of one of the famous arts of Kanazawa.” I fastened the brilliantly colored toy ball onto my backpack, and a bell inside jingled as we continued walking to our ultimate destination: a modest store located around the corner from the market.

Here an 81-year-old man named Mr. Meboso Hachirobei carried on his family’s tradition – tying fishing flies and lures – dating back five generations, when the area was called the Kaga Province and samurai warriors were the only locals permitted to fish in Kanazawa’s rivers.

In planning my first trip to Japan, I was drawn to Kanazawa, a city of about 500,000 on the west coast of the main island Honshu.

For starters, it offered a less-traveled slice of the country – “The Real Japan” as one tourist brochure proudly proclaimed -- an alternative to Kyoto, the place everyone told me I HAD to see. But when I discovered the website for Mr. Meboso’s store, which featured images of masterfully tied “Kaga-style” fishing flies hovering above Japanese descriptions, I knew I had to visit.

Call it a passion, call it a curse, but fishing haunts me, consumes my thoughts, and often eludes me. I seem to emerge from many a river empty-handed. Why can’t I just travel to a place and enjoy it without thinking about fish? Ever since I picked up a fly rod during my college days in Colorado, my travels have revolved around this bittersweet love.

The main fish market in Kanazawa.

For this particular mission, though, I needed some local help. I contacted the Kanazawa Goodwill Guides Network, a non-profit organization that provides free guides and interpreters for tourists. A few days later, I received an email from my new tour guide, Shinji Koshida.

“I, Mr. Koshida, retired banker, am pleased to accompany you to meet Mr. Meboso Hachirobei. Many traditional arts and crafts developed in Kanazawa through the long history, one of which is Kaga fly-fishing lures.”

Mr. Shinji Koshida, volunteer tour guide in Kanazawa.

Mr. Koshida wanted some information from me, too. “I do not know much about Kaga fly, so please let me know what questions you have for Meboso Hachirobei. I myself then prepare and study.”

I emailed a list of questions the next morning, and a day later I flew from New York to Japan. After brief stays in Tokyo and Hiroshima, I arrived in Kanazawa on board a bullet train called Thunderbird.

It was a delight to check into my ryokan, a traditional family-run inn, where I was shown to a Japanese-style room with rice-paper screen doors, a low wooden table with a pot of hot tea, and a futon, which was rolled onto the tatami mat floor each evening for me to sleep on.

That first night in Kanazawa, I had time to explore some of the city, which was a mix of old and new, with ancient geisha districts abutting modern streets with fashionable shops. I walked past the UFO-shaped 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, stumbled upon an alleyway and made a key discovery.

Ryokan, Kanazawa.

Bar Caprice was located in Kanazawa’s Kakinokibatake shopping district, sandwiched between a sushi den and ramen shop. The place reminded me of an old-school Manhattan watering hole with four tables, nine bar stools and a wood-weathered bar.

For the next hour, I enjoyed Japanese whiskey served by a chatty bartender named Naoki Saida, who wore a crisp white shirt and black vest. Despite the fact that I didn’t know Japanese and Naoki only spoke a bit of English, we found common ground. Both of us are baseball fans.

“Do you know Matsui?” he asked.

“Of course. Everyone in New York knows about Matsui. He played for the Yankees.”

“He is from Ishikawa Prefecture! From a town called Neagiri in the south,” Naoki said. “He played high school baseball in Kanazawa.”

Naoki then demonstrated Matsui’s intimidating batting stance. Behind the bar, he stood erect and still, his hands holding an imaginary baseball bat, his shoulders twitching slightly, eyes focused straight ahead on the pitcher.

It was the best Matsui impersonation ever, but that sushi place next door was calling my name. I thanked Naoki and stepped toward the door. As Kanazawa is notorious for its constant rain, it was now pouring outside.

“Wait!” Naoki said. He came around the bar and handed me his umbrella.

“I can’t accept this.”

“It’s present,” he said, before bear-hugging me goodnight.

The next morning, Mr. Koshida picked me up at my ryokan and we walked together to Mr. Meboso’s store.

Mr. Meboso's fly tying materials.

Mr. Meboso welcomed us with handshakes and led us to a handsome wooden table in the back, where we sat together next to floor-to-ceiling boxes filled with fishing flies. With Mr. Koshida as interpreter, Mr. Meboso traced the store’s history back to its founding in 1575.

“We made sewing needles,” Mr. Meboso said, humbly.

Each generation has maintained both the store and name: Meboso Hachirobei. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that the family got into the fly-tying business.

“The 16th generation Meboso Hachirobei was the first to make Kaga fishing flies,” said Mr. Meboso, who is 19th generation. “And today we continue the tradition.”

Mr. Meboso held before us a box made of mahogany wood. He unlocked a gold-colored latch, which revealed a blue cloth covering dozens of fishing flies, organized neatly by size, five rows on each side of the box, with about 16 flies per row, all meant to replicate underwater insects or nymphs.

“Samurai warriors would often go fishing for ayu (or sweetfish) to build up their bodies and their physiques,” said Mr. Meboso. “At the time the rivers were rocky and water ran so rapidly. Walking and holding a long fishing rod in the river was a tough exercise!”

Mr. Meboso spoke softly in Japanese, a reflection of the delicateness surrounding him. Spread on the table were bird and peacock feathers colored metallic blue, yellow and pink; tinsel and threads; and even the translucent skin of a snake found in the local mountains.

Mr. Hachirobei Meboso.

“This glistens in the water,” Mr. Meboso said as he demonstrated how a tiny square-sized piece of snake skin is attached with tweezers to the shank of the fishing hook. “It attracts the attention of the sweetfish.”

Today, the shop makes about 700 different types of flies, ranging in price from 500 yen to 1000 yen (about $5 to $10).

“All the Kaga flies share a common feature,” Mr. Meboso said. “Here, we paint the eye of the hook with gold leaf,” a technique that reflects the history of arts and crafts in Kanazawa, where thanks to climate and water quality, more than 99 percent of Japan’s metal leaf is produced.

I could tell Mr. Koshida was enjoying the chat as much as I was. He had printouts of an interview he’d conducted with Mr. Meboso before I had arrived, using the questions I emailed him.

“I am from Kanazawa, but I did not know about Kaga fishing flies before today,” Mr. Koshida exclaimed with a sly smirk. “This is very interesting to me!”

Before leaving, I bought a selection of flies – including a few geared for sweetfish – and asked Mr. Meboso for advice on where to fish in Kanazawa. I broke out a city map, and he circled a pedestrian bridge spanning the Asanogawa River in the northwest part of town.

Tenkara fishing in the Asanogawa River.

“This is where I go to fish sometimes,” he said. “It’s not the best season for fishing now. That is in August. But you can still go there.”

I found myself at this spot on my last full day in the city, after borrowing a bicycle from my ryokan and riding through the serpentine streets of the old samurai district.

I unpacked my new tenkara fishing rod and hoped I would remember the tricky new knots I learned from the guys back at my local fly shop in NYC. This was the Japanese style of fishing which employs only a rod, line and fly – but no reel. The method is simple, the equipment minimal. It seemed appropriate for this trip.

As I tied on a fly and got ready to fish, I recalled what Mr. Meboso had told me a day before, how samurai would often fish these rivers without using a hook, and still they would catch fish.

“Fishing trained the mental powers of the samurai,” he said. “The samurai would concentrate on the spirit of the fish not to swim away.”

It’s hard to believe that technique worked, but Mr. Meboso was not one to doubt. Holding the line in my left hand, I raised the tip of my 10-foot rod to the sky and flicked my right wrist. The line uncoiled, and a fly gently fell to the surface.

There were sweetfish in the river, and I could feel them rising.

-- Andrew Tarica

Kanazawa – If You Go

Getting There: The Hokuriku Shinkansen (bullet train) runs daily between Tokyo and Kanazawa. Travel time is about 2 ½ hours. Kanazawa’s centrally located train station is considered one of the most beautiful in all of Japan.

Staying There: Sumiyoshiya Ryokan, located 5 minutes by bus from the city’s train station, has been in existence for about 300 years and offers comfortable accommodations in the heart of Kanazawa. Rooms are 6,900 yen to 12,600 yen (about $57 to $105) with breakfast and dinner optional (but highly recommended).

Eating There: Kanazawa is famous for its seafood and sushi. There are dozens of small restaurants and sushi stalls in the Ohmicho fish market – keep your eyes peeled for the grilled giant prawns. Another great spot is Sushi Ippei, located at 1-5-29 Katamachi, a family-run restaurant that has been open since 1947. Noodle fans should try Ippudo Ramen, a Japanese chain with an outpost in the Kakinokibatake district. Bar Caprice, a cozy spot to try Japanese whiskey, is located a few doors away.

Fishing There: There is decent DIY fishing for ayu (sweetfish) in both the Asanogawa and Saigawa Rivers. The best time of year is July and August. A good, albeit urban spot is underneath the pedestrian bridge on the Asanogawa near the Kazue-machi Chaya District; there is fishing both upstream and down. Pick up flies from Meboso Hachirobei Shoten, located at 11-35 Yasue-cho, Kanazawa.

Contact: For more information or to arrange a guide, contact the Kanazawa Goodwill Guide Network at http://kggn.sakura.ne.jp/profile_e.html.

- end -