Steve Davis, a carrier along the world's longest mail run, prepares to make a mail drop in the Outback.

Link To Another World

Mail bonding in the Australian Outback

By Andrew Tarica

The red-dirt runway appears as a mirage amidst a wasteland of barren mountains and endless desert.

Piloting what may be the world’s most grueling mail run, Steve Davis readies his Aero Commander 688S for a landing at the Moolatwanna sheep station, in the heart of Australia’s impressively empty Outback.

Seconds later, as the plane lands, tires screech on the sand, rocks and weeds of the runway. Off in the distance, a gray Land Cruiser rumbled toward the landing strip, sending dust from the Strezlecki Desert into the brilliant, blue sky.

“G’day, Steve. It’s nice see you again,” says Audrey Sheehan, as Davis piles from the plane to deliver the Moolatwanna mailbag. In return, Sheehan hands him a bag of outgoing mail.

Wearing a blue blouse, sandals and a wide-brimmed leather hat, Sheehan owns the ranch along with her husband Mike. At 485 square miles, Moolatwanna is the smallest property along the Channel Mail Run — a weekly route that provides service to more than two dozen small towns and stations (or ranches) in the Australian interior.

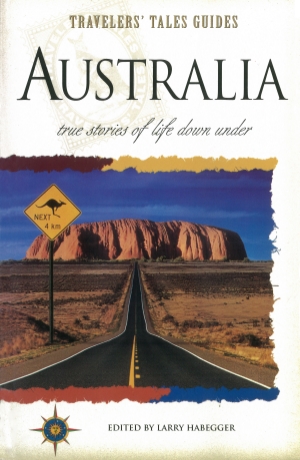

This story appeared in the anthology Australia: True Stories Of Life Down Under, a Travelers' Tales Guide, published in 2000.

Covered with dust, I step off the plane after Davis. I am just along for the ride, taking part in a “tour” offered by Augusta Airways, the carrier contracted by Australia Post to make deliveries to some of the most remote mailboxes in the land Down Under. In all, there are about a dozen mail runs serving the Outback, and a few tourists are allowed on each ride.

From my perspective, I’ve chosen the most intriguing of the tours. Billed as the “world’s longest,” the Channel Mail Run serves a forgotten, 1,800-mile stretch of desolate land, where distance and isolation have created an environment that only people of the utmost strength and resourcefulness can call home.

As Davis puts it, “It takes a different breed to live out here.” Indeed, Port August — the nearest population center as well as the jump-off point for the mail run — seems a world away.

Every Saturday morning, the mail plane heads north from Port Augusta’s small airport, and every Sunday night it returns. Along the way, it traverses the Great Artesian Basin, perhaps the world’s greatest reservoir.

“That’s why it’s called the Channel Mail Run,” says Deb Grantham, an employee of Augusta Airways. “When it rains in northern Queensland, the rains come down in channels and flood the inland desert areas.” This runoff — along the Cooper Creek and the Diamintina and Georgina river systems — occurs across a staggering 800,000 square miles of arid land.

As I later learn, the floods are both an omen and a blessing. While water is essential for raising cattle and sheep, it also leaves ranches and towns isolated for days, weeks, even months.

Wayne Daley and family are more than 100 miles from their nearest neighbor.

This is bad news for people such as John Talbott, who seems to embody the spirit of the Outback, with his hand-rolled cigarettes, Blundstone boots, blue jeans and wide-brimmed cowboy hat.

Talbott lives with his wife and two children at Durham Downs, a 4,000-square-mile cattle ranch on the banks of Cooper Creek, at the edge of the Sturt Stony Desert. In a sentiment shared by many, Talbott says he treasures the isolation that comes with living near the center of the world’s flattest and driest continent.

“I love it out here,” he explains, offering a one-word reason: “peace.”

Despite the seclusion, there seems to be an intense sense of community among the towns and stations along the Channel Mail Run. Most people I meet in this vast land either know each other, know of each other or have some common acquaintance.

“Out here you know everyone,” says Allison Bammann, a gardener at the 12,500-square-mile Innamincka Station. “Down at the pub, we’re pretty much the only people there, and we can have parties just for the people who work at the stations around here. It’s great.”

Or is it? As Talbott points out, there is one obstacle to Outback life, and it’s neither the intense heat nor the unbearable bush flies, which buzz around his eyes, ears, nose and mouth as he speaks.

For this cowboy, the one “crook” thing about life in the Channel Country is, simply, “I’ve got to drive 150 miles to the nearest pub!”

That would be the Birdsville Hotel, a 112-year-old watering hole in the tiny town that bears its name. Inside is a wall decorated with dozens of wide-brimmed hats, all torn, tattered and frayed, with names of their former owners: Highway Jimmy, Chopper Tony, Bazaa Skolee, Dylan Stoddy, Pee Wee Clark.

“You’ve got to live out here at least a year before you get your hat on the wall,” says Richard Calliss, bartender at the pub, which is just across the street from the airstrip. Birdsville is one of five towns on the mail run, along with Leigh Creek, Innamincka, Bedourie and Boulia — the unofficial extraterrestrial capital of the Outback.

For decades, residents of this town (population: 250), where we spend a night, have been baffled by a strange phenomenon called the Min Min Lights. Appaerently, the Min Mins are ghostly luminous lights, which float through the air as if someone is carrying a lantern in the mist. Yet no one has managed to capture or photograph them.

Talk to Tania Tully, co-owner of the Australian Hotel, and she’ll tell you the Min Min Lights are merely liquid-induced lies. “The best way to see the Mins Mins,” she says, “is to grab a seat at the bar and start drinking the rum.” So I take her advice and even increase my odds by drinking a stubby (or bottle) of Australian lager. But much to my dismay, after climbing atop the water tower on the outskirts of town for a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape, I see nothing.

Tania’s husband John has had better luck. “Yeah, I’ve seen them — twice — when I was a boy,” he explains. “I was camping with a bunch of my friends. At first we thought it was a car coming toward us in the distance, but it never got any closer.”

Over the years, there have been many guesses, theories and explanations (fire flies, birds covered in fungi, moor mirages…), but as of yet, none have disproved the Min Min phenomenon. As John Tully says, with not a shot of rum in his hand, “Yup, the Min Mins are out there. They’re definitely out there.”

Some might say, though, that the only thing “out there” are the folks who live in Australia’s interior. Yet for all its isolation and hardship, the Outback is becoming more mainstream for some of its inhabitants.

The boots of a ringer (or rancher) near Innamincka are a testament to the harsh conditions.

“Up until a few years ago, all the communication was by high-frequency radio, which wasn’t all that good,” Davis says. “It used to break down a lot. Now they have television, radio and last year they got telephones. Some people even have fax machines!”

But make no mistake — this is a wild, unpredictable country, and there are still times when Mother Nature takes the upper hand. Our return flight from Boulia is a case in point. Sudden rains on the Queensland coast have triggered floods in the Channel Country, and the muddy waters of the Cooper River are threatening to keep the town of Bedourie and a few ranches isolated for months.

During such a crisis, the mail runs take on added importance. As Bedourie’s Jim Smith says, “We’ve got telephones now, but apart from that, we really got nothing. We don’t even have newspapers. Most people rely on the mail service. They call it an essential service.”

Pee Wee Clark, station manager at Glengyle, which is also besieged by floods, echoes the sentiment.

“Mate, we would really be stranded without the mail runs,” he says, after Davis flies in mail, as well as disaster supplies such as groceries, newspapers and, of course, beer (courtesy of the Birdsville Pub). “Seriously, if we ever lost this service, we might as well roll up our swags and leave.”

Which is exactly what Davis plans to do. Leave his job, that is. Once Davis, 36, makes his final pickup at Leigh Creek on the way home, he is officially an ex-pilot of the Channel Mail Run. His new job will be with the Royal Flying Doctor Service, working out of Alice Springs. He admits that exhaustion played a role in his resignation.

“This mail run is crazy,” Davis says. “By the time I get home, I’ve made 56 landings and takeoffs in two days. And by the end of the weekend, I’ve used up as much adrenaline as most pilots do in a year.”

Personally, I’m just along for the ride, but by the time we touch down in Port Augusta, my pillow is calling. Yet I feel exhilaration as well — from the stark, almost haunting beauty harbored in the huge skies and timeless landscape of the Channel Country; the opportunity to share time with a community of people who don’t get many visitors; and the chance to see how vital communication is in a place such as the Outback.

As Steve Davis explains, with bags under his eyes and sweat on his brow, “The thing we try and get across to people is that this really isn’t a tour. It’s a mail run. A fair dinkum mail run. And our first priority is the mail.”

Andrew Tarica is a writer and editor. Armed with only a backpack, fly rod and laptop computer, he traveled from Australia to Far Eastern Russia along the “left bank” of the Pacific Rim.